Written by Sarah Cornette.

Sarah Cornette is a CFK Africa Peacock Fellow and PhD student in Education at UNC Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on community-based participatory research, arts-based methodologies and youth empowerment, particularly among marginalized populations, migrants, and refugee communities.

I came to Kibera as a CFK Africa Peacock Fellow to facilitate a series of participatory art sessions with teenage mothers—spaces shaped not by curriculum, but by care, co-creation, and choice.

The teen moms trickled in slowly. A couple arrived early, with backpacks, battered textbooks, and shy but ready smiles. Thirty minutes later, a couple more showed up, balancing infants on their hips. I offered to hold a baby so his mother could begin creating her name tag and sketchbook. As I swayed and bounced him in practiced arms, other teens arrived—but in the end, only sixteen of the expected 24 showed up.

It’s easy to measure attendance. Harder to measure what it takes to attend. These young mothers live within layered forms of precarity: caregiving, school demands, food insecurity, and the constant shadow of gender-based violence. Even among the 200+ teenage mothers in CFK’s Funzo program, just reaching a session like this one can feel like a victory.

There’s something about working in a space shaped by both trauma and impermanence that demands a different kind of posture. Not the Western urgency of outcomes. Not the pressure of deliverables. But something slower, humbler.

A kind of presence that listens before it speaks.

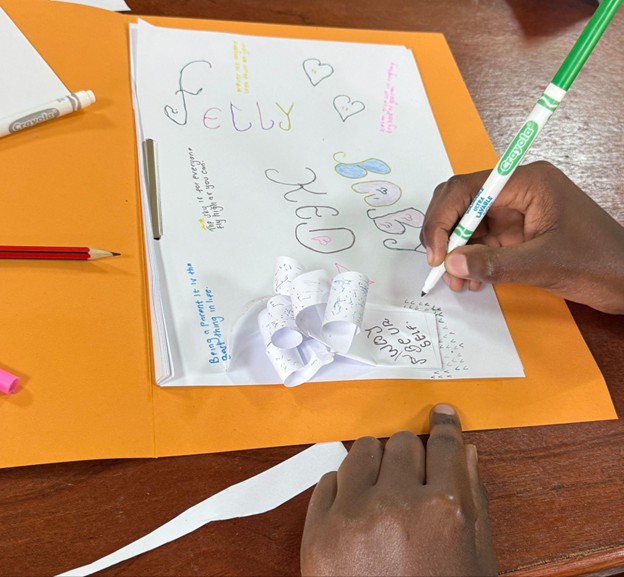

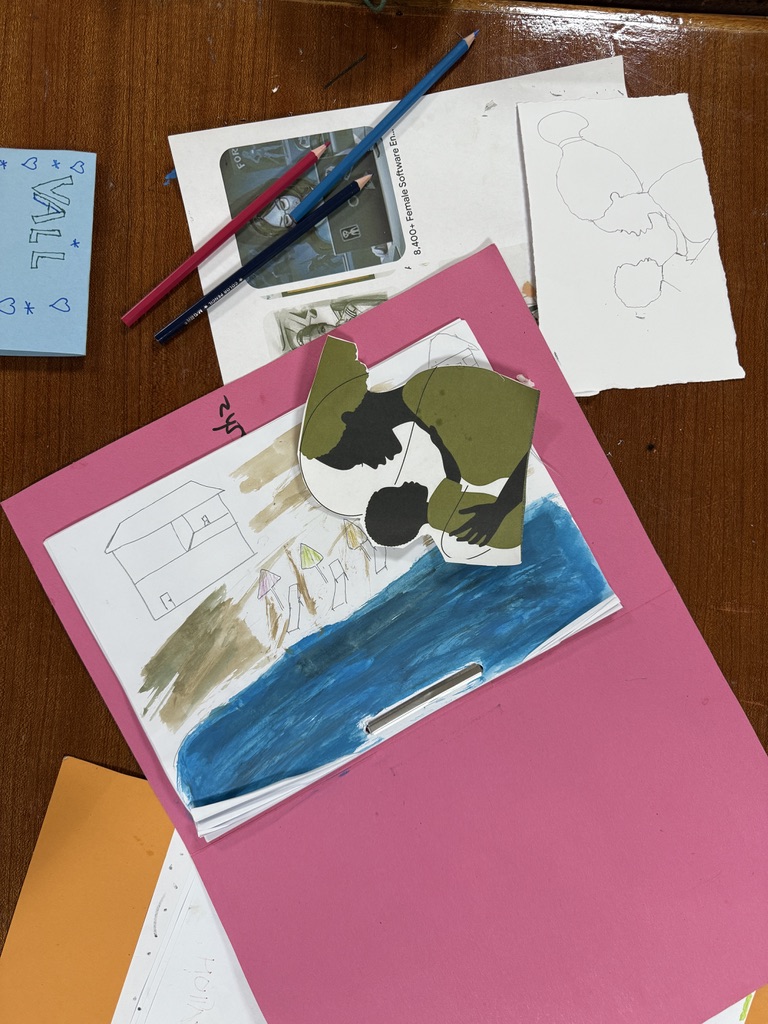

In our first session, we offered a few simple materials—colored drawing materials, copy paper, and cardboard folders. The teen moms created name cards with symbols of strength on them: butterflies, their children, hearts symbolizing love of–and for–family. We made sketchbooks simply, from copypaper and folder covers—creating a private space for reflection and exploration that need not be shared with anyone.

Everyone in the room worked together, including CFK staff and me, to observe a few artworks, share what makes us feel strong, and explore the materials. Halfway through the session, I stepped back and invited the young mothers to take the lead on discussing logistics and shaping next steps, while I shifted into the role of note-taker and observer. In that moment, the nature of the project came into clearer focus.

It’s not art therapy, though that was my first career, and certainly my work is informed by principles of trauma-informed practice. It’s not a structured curriculum—the participants will always be able to choose what they make, and how much they want to share. It’s not even about “resilience” in the way we sometimes name it from the outside. It’s about making something—even a mess—together. It’s about creating a space where, for just a little while, a teen mom can be more than a statistic or a story of survival. She can be curious. She can be seen. She has control.

Even that is complicated.

We offer snacks. Art supplies. We promise care and consistency. But the girls have learned, over and over, that things (and people) come—and go. I have to ask myself daily: Am I showing up in a way that builds trust, or replays a pattern?

We talk a lot in Western contexts about accountability. But here, accountability has to move both ways. When a girl doesn’t come one week, I can’t assume disinterest. I have to ask: what did it take for her to come last time?

And if she does show up, how will I meet her?

With structure, yes. But also with flexibility. With eyes open for who she is that day—not who I expected her to be. With materials that invite, rather than prescribe. With the readiness to hold a baby, sit on the floor, and adapt. Above all, with love.

Sometimes I want to do more. Reach more. Know that the project will last, scale, replicate. But I’m learning to release that. The ethics of this work aren’t about reach. They’re about relationship.

So I keep showing up.

With snacks, scissors, and an ever-expanding array of recycled materials from the environment in Kibera.

With structure that invites, and softness that doesn’t demand.

Not because it’s enough. But because it’s what I can offer—and because they came.